Zygoma Plus: New Technique - PART 2

Zygomatic Implants Techniques Overview, Design Response and Considerations for Routine Mainstream Implementation in Maxillary Implant-based Rehabilitation

The consideration of Zygoma implants is typically thought to be reserved only for severe maxillary bone defects such as those following hemi-maxillectomies, or in non-oncological presentations severe atrophy from long term edentulism and denture wearing. However, bone atrophy is not the only contributor to a lack of bone in the maxilla. Other osseo-destructive mechanisms include odontogenic pathology, sinus anatomy and pneumatization following extraction 1 , as well as iatrogenic factors (failed prior treatments), and may well be present in dentate individuals with terminal or dysfunctional dentitions.

In such patients, early planning and treatment, which may include Zygomatic implants, before they face full edentulism can be highly advantageous not only through halting the progression of odontogenic diseases and its associated additional surgical constraints, but also in a patient’s journey and physical, mental and social wellbeing. Early treatment offers additional means of controlling the outcome both surgical and restorative, as well as a significant improvement in the patient experience and quality of life 2.

Traditionally the advanced and invasive nature of Zygomatic implants and suspected complications historically reported in the literature 3 4 5 have led to a reluctance by clinicians to use this method before other alternatives have been all but exhausted.

However, when anatomical, biological, pathological, occlusal, or other constraints exist, which may strain traditional implant treatment to the limits of its bioadaptive capacity 4 5 , a new technique with Zygomatic implants may offer a more definitive alternative by working well within its limitations and a better controlled biomechanical equilibrium.

Discussion

The reluctance by clinicians to use Zygomas as a first-line mainstream modality is due to the advanced nature of this procedure with no formal training paths 8 9 for clinicians to gain proficiency as well as suspected or reported complications 3 4 5 .

Some of the reported complications are attributable to systemic, behavioral, idiopathic or iatrogenic factors and are common to all implant treatments. Biologic/surgical complications that are unique to Zygomatic implants include sinusitis, oro-antral communication, buccal dehiscence, vestibular mucositis and external periorbital fistula associated with infection of the implant tip. Whilst the prevalence of these complications is generally low, they are significant due to the more advanced and invasive nature of these procedures.

The more common complications are not of a biologic nature and are not well documented in the literature. These include discomfort and hampered hygiene due to the bulkiness associated with a palatal emergence of the traditional techniques, as well as prosthetic complications due to a lack of restorative space. These non-biologic complications are significant factors that compound the aforementioned biologic/surgical risks and further dissuade clinicians from using Zygomas.

The etiology of most complications that are unique to Zygomatic implants can be divided into the following groups:

(i) Implant Design & Instrumentation

Features of the original and other common Zygoma implant designs include,

a. Coronal threads and a treated surface reduces the efficacy of managing coronal bone loss and/or exposure;

b. Implant tip design with a hollow section (originally designed to provide a mechanical bone lock after healing) is a potential trap for bacteria from the sinus in the event of a breach during insertion and can result in infection surrounding the implant tip with subsequent periorbital fistulation;

c. An implant mount with a diameter that exceeds the diameter of the body of the implant restricts the depth of insertion when this meets the crestal or palatal bone leading to a palatal emergence of the implant;

d. The diameter of the implant can be problematic in situations when the Zygomatic bone is narrow, and reduces the separation between adjacent Zygoma implants in quad cases.

(ii) Surgical Technique

Other than the importance of adhering to parameters that are common to all implant osteotomy procedures, such as cooling and implant stability, when placing Zygoma implants intraoperative choices and the surgical technique itself may contribute to complications through one of the following mechanisms:

a. The implant protruding into/through the sinus space without separation. In this situation the implant is a foreign body within the sinus and may cause or contribute to sinus pathologies and oro-antral fistula, especially if the surface of the implant is rough or threaded;

b. The implant protruding outside the maxillary bone into thin non-keratinised vestibular tissues risking mucositis, dehiscence and exposure, especially if positioned shallow;

c. Poor positioning of the implant head (too palatal and/or too shallow) without an alveolectomy (if required). Other than restorative issues, this may also result in hampered hygiene and the repercussions thereof including coronal inflammation, bone loss and being in the vicinity of the floor of the sinus it may also contribute to oroantral communication.

Much effort has been expanded in order to overcome the known complications with modifications to the design of Zygoma implants, as well as modifications to the techniques. Most of the current implant designs have done away with a hollow channel at the apex. The ZAGA implants have additionally improved the apical design with a varied taper to better engage the zygomatic bone internally from within the sinus as well as at the external cortex and a polished tip, which protrudes through the zygomatic bone.

ZAGA implants are also less bulky than most of the other available Zygoma implant designs, have polished body, a 55º angle correction and a mount of the same diameter as the implant body for improved flexibility in idealizing the position of the implant and prosthetic access channel.

Since the vast majority of complications are associated with the coronal half of the implants, this has been the primary focus of the design response, but it must be considered hand in hand with the surgical technique, which varies. Primarily there are two schools of thought:

Technique & Design Response A:

Conservative alveolar and intra-sinus preparation with preservation of sinus lining whilst adhering to the concept of bi-cortical stabilization.

Technique: Conservative preparation of the implant trajectory on the lateral aspect of the maxilla, intra-sinus placement and preserving the sinus mucosa helps in reducing complications such as sinusitis, and buccal dehiscence. However, being conservative on the coronal aspect by avoiding an alveolectomy in order to facilitate bicortical fixation comes at the expense of a lack of restorative space and palatal emergence of the implants, thus the complications associated with those factors, as noted above, are not eliminated.

Implant Design: For effective bicortical stabilization the coronal part of the implant should have threads, such as in ZAGA round, but this can become problematic in managing hygiene and peri-implant health in certain cases in the event of crestal bone loss, as noted earlier. ZAGA round may be suitable in cases that have adequate crestal bone after an alveolectomy, as may be required, provided that the threads are fully encased in bone and do not protrude into the sinus (unless grafted).

The question of bicortical stabilization is highly debatable. In the first instance it should be noted that the original Zygoma implants were introduced by PI Branemark for maxillectomy cases and did not rely on any kind of stabilization at the coronal aspect of the implant. It should also be noted that two cortices already exist: an internal/sinus cortex and an external cortex of the zygoma, and in all zygoma techniques the implant transverses through both cortices. The palatal/crestal bone offer an additional stabilization, but it is a tertiary point of stabilization, and is unlikely to offer a significant advantage when the zygoma implant is connected to the other implants in a group through a rigid structure such as a titanium frame. What is traditionally referred to as bi-cortical stabilization could in fact be a hinderance when restorative space and implant positions are compromised in order to facilitate this technique.

Without focusing on a tertiary fixation point at the crest, the surgeon is free to improve restorative space with an alveolectomy and/or sinus crush, and to position the implant according to the restorative needs. However, with the only fixation being in the Zygomatic bone, the length of the implant may be a factor allowing flexure and potentially a disturbed adaptation at the coronal aspect. It is therefore important to control the biting forces during the initial 6 months of healing with occlusal adjustment avoiding heavy posterior contacts, avoiding long cantilevers, canine or anterior guidance with disclusion of the posterior segments on any excursive movement, and also by considering administration of neurotoxin to the masseters and temporalis muscles to reduce natural clenching power.

Technique and Design Response B:

Conservative extra-maxillary placement with minimal or no sinus involvement.

Technique: Extra-maxillary placement of the Zygoma implants may be used in order to optimize the emergence of the prosthetic screw channel and eliminate sinus-related complications. The main disadvantage of this technique is the risk of a dehiscence in the buccal sulcus and a lack of restorative space, especially with conservative shallow placement in the absence of an alveolectomy resulting in an increase of the gap between the implant and lateral wall of the maxilla.

This technique is more often required in cases with severe atrophy requiring quad zygoma, and is less susceptible to dehiscence with deeper placement, reduction of the gap between the implant and lateral aspect of the maxilla, and appropriate management of any dead space.

Implant Design: The ZAGA Flat is an ideal response to this technique due to its narrower profile, flat buccal aspect, and polished surface to the implant collar.

Zygoma Plus – A New Concept

Advancements in implant design, such as ZAGA Round and ZAGA Flat, not only reduce the traditional risks, but in fact offer a far more predictable solution when coupled with an appropriate technique that respects the anatomy and biological nature of osseointegration.

In this report a new technique referred to as Zygoma Plus was shown, which is aimed to substantially reduce all the complications that are uniquely associated with other Zygoma techniques by relying on variations of well documented and proven individual procedures.

Whilst being surgically conservative has advantages in the initial healing and physiological response to the iatrogenic trauma, when failing to provide the requisite conditions for success at surgery conservatism may interact with the concept of offering a definitive solution and long term success in terms of aesthetics, biostability, cleanability, durability, function and comfort.

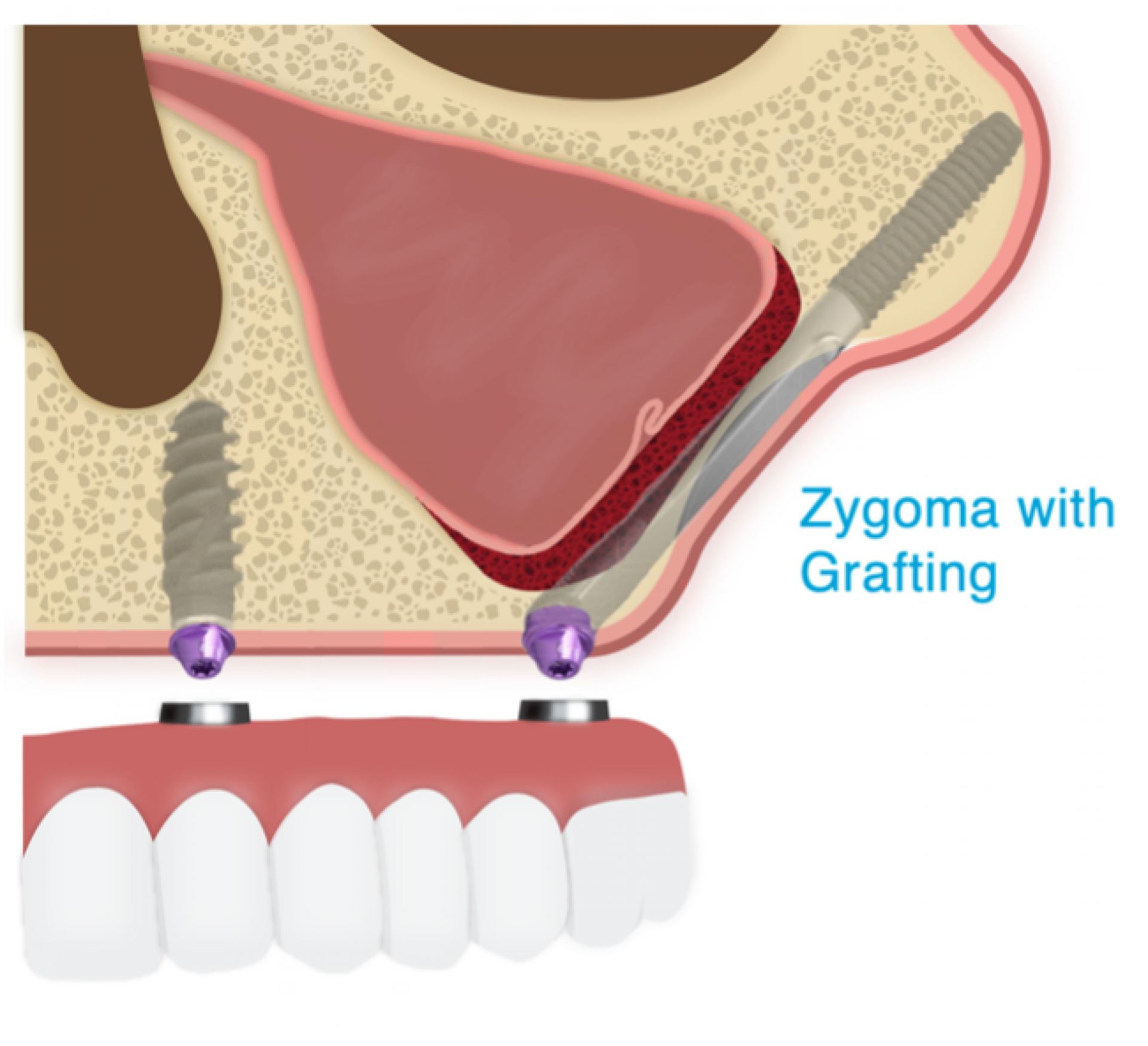

In concept, Zygoma Plus represents conservatism to the extent possible while placing a balanced emphasis on creating the requisite conditions for a definitive solution with an alveolectomy as may be required for restorative space, sinus grafting, optimised implant positioning, soft tissue management and fitting of reliable teeth.

Every situation is different and the concept of Zygoma Plus may necessarily involve elements of extra-maxillary placement and/or intra-sinus placement whilst always controlling the surgical situations with adjunctive hard and soft tissue management techniques, and controlling the restorative and biomechanical situation with the fitting of immediate final teeth supported by a rigid milled titanium frame.

Basic surgical features of the Zygoma Plus technique include:

Hockey stick anteroplasty

This technique offers improved yet conservative instrumentation and preservation of the sinus mucosa at the sinus floor and along the implant trajectory, as well as exploration of the internal curvature of the zygoma bone to determine an appropriate entry point. The conservative vertical slot allows for a close adaptation of the implant to the bony edges and in certain cases offers additional stabilization of the implant. The close adaptation of the implant also blocks the lateral antrostomy acting as a barrier protecting the grafts and tissues medial to it. It reduces the biologic strain and facilitates ossseointegration along the shaft of the implant.

Dual-layered sinus grafting

BioOss Collagen is used as a liner against the sinus mucosa due to its softness and membrane-like cohesiveness, as well as its documented success in the sinus space. However, during instrumentation and drilling with water the BioOss Collagen may become fluffy and escape. For this reason a second layer using Nanobone is applied, which does not flush with water and a firmer material which does not flush with water, confines the BioOss and creates a firmer base for the Zygoma drilling process.

Alveolectomy and/or Sinus Crush Alveoplasty

In many dentate or partially dentate cases, as well as combination syndromes due to long term denture wearing and pneumitisation of the sinuses, bone leveling is required in order to create the required restorative space for an aesthetic, hygienic, comfortable and durable supra-structure. The bulk alveolectomy is performed using Rongers, and the bone is then levelled using a pear-shaped bur. When the sinuses are pneumatized, the required leveling may be encroach beyond the floor of sinus, which is managed by grafting the sub-antral space before apical impaction of the sinus floor to the desired level (sinus crush).

Idealised coronal placement

The alveolar entry point for the implant osteotomy is idealized to ensure emergence of the prosthetic access hole through the central fossa of sites 5 or 6. The path towards the cheekbone is then determine to optimize encasement of the tip of the implant within the cheekbone, whilst at the same time ensuring the closest possible adaptation of the implant to the lateral wall of the sinus. Such adaptation is often facilitated by an alveolectomy (as required).

Soft Tissue Management

An alveolectomy also results in an excess of palatal soft tissues. The connective tissue of the palate is trimmed to allow adaptation of the keratinized palatal mucosa over the ridge for improve biotype and stability of the periimplant mucosa as well as to improve hygiene.

Disclaimer:

The author has no commercial interest in any of the brands described in this report. The report represents an opinion based on extensive experience using Zygoma Plus procedures and a 7-year follow-up period. Experience is a critical factor in all Zygoma procedures, and these procedures can only be considered for routine implementation by highly experiences clinicians who routinely (or exclusively) perform advanced implant and bone augmentation procedures.

CITED LITERATURE

1 Marília Cabral Cavalcanti et al. Maxillary sinus floor pneumatization and alveolar ridge resorption after tooth loss: a cross-sectional study. Braz Oral Res 2018 Aug 6; vol32.0064.

2 Outcomes Assessment of Treating Completely Edentulous Patients with a Fixed Implant-Supported Profile Prosthesis Utilizing a Graftless Approach. Part 2: Patient-Related Outcomes. Alzoubi F, Bedrossian E, Wong A, Ferrell D, Park C, Indresano T.Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2017 Sep/Oct;32(5):1080-1085. doi: 10.11607/jomi.5521.PMID: 28906505

3 Surgical complications in zygomatic implants: A systematic review. Molinero-Mourelle P, Baca-Gonzalez L, Gao B, Saez-Alcaide LM, Helm A, Lopez-Quiles J.Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2016 Nov 1;21(6):e751-e757. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21357.

4 Survival and Complications of Zygomatic Implants: An Updated Systematic Review. Chrcanovic BR, Albrektsson T, Wennerberg A.J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Oct;74(10):1949-64. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.06.166. Epub 2016 Jun 18.

5 Immediate loading of zygomatic implants: A systematic review of implant survival, prosthesis survival and potential complications. Tuminelli FJ, Walter LR, Neugarten J, Bedrossian E.Eur J Oral Implantol. 2017;10 Suppl 1:79-87.

6 Occlusal considerations in implant therapy: clinical guidelines with biomechanical rationale. Kim Y, Oh TJ, Misch CE, Wang HL.Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005 Feb;16(1):26-35.

7 Influence of forces on peri-implant bone. Isidor F.Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006 Oct;17 Suppl 2:8-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01360.x.

8 Challenges in dental implant provision and its management in general dental practice. Jayachandran S, Walmsley AD, Hill K.J Dent. 2020 Aug;99:103414. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103414. Epub 2020 Jun 22.

9 A global perspective on implant education: Cluster analysis of the "first dental implant experience" of dentists from 84 nationalities. Dragan IF, Pirc M, Rizea C, Yao J, Acharya A, Mattheos N.Eur J Dent Educ. 2019 Aug;23(3):251-265. doi: 10.1111/eje.12426. Epub 2019 Feb 15.

OTHER LITERATURE

Literature

ZYGOMA TECHNIQUE

Parel S, Branemark P-I, Ohrnell L, Svensson B. Remote implant anchorage for the rehabilitation of maxillary defects. J Prostate Dent 2001; 86:377-381

Tamura H, Sasaki K, Watahiki R. Primary insertion of implants in the zygomatic bone following subtotal matxillectomy. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 2000; Feb: 41(1):21-24

Bedrossian E, Stumpel L, Beckley M, Indresano T. The zygomatic implant: Preliminary data on treatment of severely resorbed maxillae. Int J oral Maxillofac Implants 2002; 17:861-865

Balshi SF, Wolfinger G, Balshi TJ. A retrospective analysis of 110 Zygomatic implants in a single stage immediate loading protocol. Int J oral Maxillofac Implants 2009; 24(2):335-341

ZYGOMA COMPLICATIONS

Quality assessment of systematic reviews regarding the effectiveness of zygomatic implants: an overview of systematic reviews. Sales PH, Gomes MV, Oliveira-Neto OB, de Lima FJ, Leão JC. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020 Jul 1;25(4):e541-e548. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23569.

Five-year outcome of a retrospective cohort study on the rehabilitation of completely edentulous atrophic maxillae with immediately loaded zygomatic implants placed extra-maxillary. Maló P, Nobre Mde A, Lopes A, Ferro A, Moss S.Eur J Oral Implantol. 2014 Autumn;7(3):267-81.PMID: 25237671

Survival and complications of zygomatic implants: a systematic review. Chrcanovic BR, Abreu MH.Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013 Jun;17(2):81-93. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0331-z. Epub 2012 May 6.PMID: 22562293 Review.

CALDWELL LUC LATERAL ANTEROSTOMY

Tatum OH. Maxillary and sinus implant reconstruction. Dental Clinics of North America 1986; 30:207-229

Garg AK, Quiñones CR. Augmentation of the maxillary sinus: A surgical technique. Practical Periodontics and Aesthetic Dentistry 1997; 9:211-219

Garg AK. Biological Process of Implant Osseointegration. Bone Biology, Harvesting, Grafting for Dental Implants 2004; p.17-18

Boyne P, James RA. Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 1980; 17:113-116

Woo I, Le BT. Maxillary sinus floor elevation: Review of anatomy and two techniques. Implant Dentistry 2004; 13(1):28-32

Zitzmann NU, Schärer P. Sinus elevation procedures in the resorbed posterior maxilla. Comparison of the crestal and lateral approaches. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics 1998; 85:8-17

SUBANTRAL GRAFTING WITH BIO-OSS

Valentini P, Abensur DJ. Maxillary sinus grafting with anorganic bovine bone: a clinical report of long-term results. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 2003; 18:556–560

Valentini P, Abensur DJ, Wenz B, Peetz M, Schenk R. Sinus grafting with porous bone mineral (Bio-Oss) for implant placement: A 5-year study on 15 patients. The International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry 2000; 20:245-253

Fugazzotto PA, Vlassis J. Long-term success of sinus augmentation using various surgical approaches and grafting materials.The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 1998; 13:52-58

Jensen OT, Shulman LB, Block MS, Iacono VJ. Report of the Sinus Consensus Conference of 1996. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 1998; 13(suppl.):5-45

Hislop WS, Finlay PM, Moos KE. A preliminary study into the uses of anorganic bone in oral and maxillofacial surgery. The British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 1993; 31:149-153

Kohout A, Simunek A, Kopecka D. Histologic Findings in Subantral Augmentation. Cesk Patol. 2006; 42(1):29-33

Piattelli M, Favero GA, Scarano A, Orsini G, Piattelli A. Bone reactions to anorganic bovine bone (Bio-Oss) used in sinus augmentation procedures: A histologic long-term report of 20 cases in humans. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 1999; 14:835–840

Hallman M, Sennerby L, Lundgren S. A clinical and histologic evaluation of implant integration in the posterior maxilla after sinus floor augmentation with autogenous bone, bovine hydroxyapatite, or a 20:80 mixture. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 2002; 17(5):635-643

Hising P, Bolin A, Branting C. Reconstruction of severely resorbed alveolar ridge crests with dental implants using a bovine bone mineral for augmentation. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 2001; 16:90–97

Tong DC, Drangsholt M, Beirne OR. A review of survival rates for implants placed in grafted maxillary sinuses using meta-analysis. The International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants 1998; 13:175-182

Yu DH. Sinus floor elevation using anorganic bovine bone matrix (OsetoGraf/N) with and without autogenous bone: A clinical histologic, radiographic, and histomorphometric analysis. Part 2 of an ongoing prospective study. Implant Dentistry June 2002; 11(2):185

Froum SJ, Tarnow DP, Wallace SS, Rohmer MR, Cho SS. Sinus floor elevation using anorganic bovine bone matrix (OsteoGraf/N) with and without autogenous bone: A clinical, histological, radiographic and histomorphometric analysis. Part 2 of an ongoing prospective study. The International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry 1998; 18:529-543